A Comprehensive Guide to the American Trial System

I chose to pen this blog because it’s important for everyone to understand exactly how our Judicial System works for the American people. Without it, there would be no due process. No trials to prove one’s guilt or innocence. Innocent people would be imprisoned. The guilty would walk away free.

Regardless of what multitudes have been led to believe, Judges are NOT radical leftists hellbent on convicting the innocent or persons they personally do not like. Judges take an oath before being sworn in that they will be impartial and unbiased with EVERY trial they oversee. Juries are NOT chosen to serve because of their political party affiliation. Vetting of the jury pool does NOT include asking potential jurors whether they’re Republican, Democrat, or Independent. Furthermore, the Prosecution and the Defense have the opportunity to ask questions of potential jurors during the vetting process, then either decline or accept them to serve on the jury in question.

GUILTY verdicts are decided by the JURY, NOT THE JUDGE, and are based on testimony and EVIDENCE presented during the trial. I take great offense with anyone who bashes this system of government, or threatens judges and/or juries simply for performing their civic duties and when the outcome doesn’t go the way they wanted it to. I worked in law enforcement for thirty years with some of those years being spent in the judicial system. To outright accuse judges and juries of any type of bias is an outright lie! I’ve received multiple summons to appear for jury duty. I’ve been selected to serve on two juries. Elected the foreperson of one. Never been asked anything political. The truth is in the details. I hope you find this article helpful.

The United States legal system is renowned for its commitment to justice, transparency, and due process. At the heart of this system lies the trial, a fundamental mechanism for resolving disputes, seeking justice for wrongs, and protecting the rights of the accused. Whether criminal or civil, trials in the U.S. follow structured procedures that are rooted in centuries-old traditions and constitutional guarantees. In this comprehensive blog post, we’ll explore how trials work in the USA, break down the steps involved, highlight the various players, and shed light on what makes the American trial system both unique and essential.

Types of Trials in the United States

Before delving into trial procedures, it’s important to understand that there are two primary types of trials in the U.S.:

- Criminal Trials: Involving accusations that someone has committed a crime, these trials determine whether the accused (the defendant) is guilty or not guilty.

- Civil Trials: These are disputes between individuals or organizations, often over contracts, property, personal injury, or family law matters. The goal is usually to obtain compensation or another remedy, not to convict someone of a crime.

While the basic structure of trials is similar, key differences exist in burden of proof, possible outcomes, and constitutional protections.

The Structure of a Trial: Step by Step

Let’s walk through a typical trial, focusing on the main stages:

1. Jury Selection (Voir Dire)

Most American trials—especially in serious criminal matters and many civil cases—are decided by a group of citizens called a jury. The process of selecting jurors, known as “voir dire,” involves questioning prospective jurors to ensure they can decide the case impartially.

- Each side (prosecution/plaintiff and defense) can challenge potential jurors for cause (e.g., obvious bias) or use a limited number of “peremptory challenges” to excuse jurors without giving a reason.

- In some cases, a judge instead of a jury hears the case; this is called a “bench trial.”

2. Opening Statements

Once a jury is impaneled (or a judge is ready in a bench trial), both sides make opening statements. These are not evidence but rather “roadmaps” of what each side intends to prove.

- The prosecution (in criminal cases) or plaintiff (in civil cases) speaks first, outlining the evidence and arguments they will present.

- The defense then presents their own overview of the case, focusing on weaknesses in the other side’s arguments or evidence.

3. Presentation of Evidence

This is the core of the trial, where both sides introduce evidence and call witnesses to support their claims or defenses.

- Direct Examination: The side who calls a witness asks initial questions.

- Cross-Examination: The opposing side then questions the witness, aiming to challenge their credibility or the facts presented.

- Physical Evidence: Documents, photographs, recordings, and other items may be introduced, subject to legal rules of admissibility.

- After the prosecution/plaintiff rests, the defense may present its own evidence and witnesses, though in criminal cases the defendant cannot be forced to testify.

4. Motions During Trial

At various points, lawyers can file motions—requests for the judge to make certain rulings. For example:

- Motion to exclude evidence that violates rules or rights.

- Motion for a directed verdict if one side believes there’s insufficient evidence to continue.

5. Closing Arguments

After all evidence is presented, both sides summarize their cases and argue why the jury (or judge) should decide in their favor. This is the last chance to persuade the decision-makers.

6. Jury Instructions

The judge gives the jury detailed instructions about the law, what standards must be met (such as “beyond a reasonable doubt” in criminal cases), and how to deliberate.

7. Jury Deliberation and Verdict

Jurors retire to a private room to discuss the case. Their deliberations are secret and can last from minutes to weeks, depending on complexity.

- In criminal cases, the verdict must usually be unanimous; in some civil cases, a majority may suffice.

- The jury’s decision is delivered in open court. In criminal cases, a “guilty” verdict can lead to sentencing, while a “not guilty” verdict acquits the defendant.

8. Sentencing (Criminal Trials Only)

If the defendant is found guilty, the judge imposes a sentence, which may include prison time, probation, fines, or other penalties. Sentencing may occur immediately or at a later hearing.

9. Post-Trial Motions and Appeals

After the verdict, the losing side may ask the judge to overturn the decision or order a new trial. If these motions fail, they can appeal to a higher court, arguing that mistakes in the trial process affected the outcome.

Key Principles That Govern Trials in the USA

Presumption of Innocence

One of the cornerstones of the American criminal justice system is the presumption of innocence—all accused individuals are considered innocent until proven guilty.

Burden of Proof

- In criminal cases, the burden is on the prosecution to prove guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

- In civil cases, the plaintiff must prove their case by a “preponderance of the evidence” (more likely than not).

Right to Counsel

Defendants in criminal cases have the right to an attorney, and if they cannot afford one, the court will appoint counsel.

Right to a Public and Speedy Trial

The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a public and speedy trial, ensuring transparency and minimizing prolonged detention.

Right to Confront Witnesses

Defendants have the right to cross-examine witnesses who testify against them.

Protection Against Self-Incrimination

Defendants cannot be forced to testify against themselves, a protection enshrined in the Fifth Amendment.

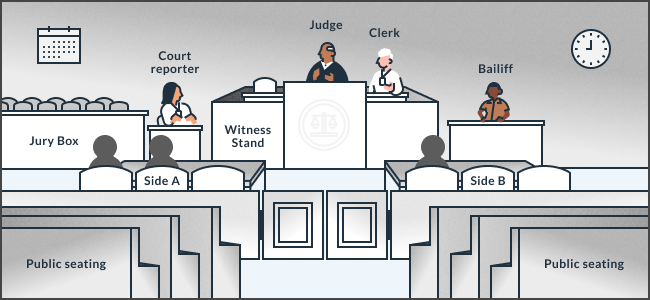

The People Involved in a Trial

- Judge: Oversees the trial, rules on legal issues, and sometimes decides the verdict in bench trials.

- Jury: A group of citizens who listen to the evidence and decide the facts of the case.

- Plaintiff or Prosecution: The party bringing the case (the government in criminal trials; an individual or entity in civil trials).

- Defense: The party responding to the case, represented by an attorney or, in rare cases, representing themselves.

- Witnesses: Individuals who provide testimony about facts relevant to the case.

- Court Reporter: Documents everything said during the trial for the record.

- Bailiff: Maintains order in the courtroom and handles logistics.

Unique Aspects of the American Trial System

- Adversarial System: Unlike some other countries, American trials are adversarial—each side presents its case vigorously, and the judge/jury acts as an impartial arbiter.

- Jury Trials: The right to a jury trial is a hallmark of the U.S. system, intended to reflect community values and provide a check on government power.

- Public Access: Most trials are open to the public, reinforcing the transparency of the justice system.

- Plea Bargaining: In criminal cases, most matters are resolved before trial through plea deals, where the accused agrees to plead guilty to lesser charges.

How Trials Begin: Filing the Case

A trial does not begin out of nowhere. For a criminal case, the process starts with an arrest, followed by charges being filed by a prosecutor. In civil cases, one party files a lawsuit (a “complaint”) against another. Preliminary hearings, discovery (exchange of information), and motions often precede the actual trial.

Appeals: What Happens If You Lose?

If a party believes the trial was unfair or the law was wrongly applied, they can appeal to a higher court. The appeals court does not re-try the case but reviews the trial record for legal errors. If an error is significant, the case can be sent back for a new trial or for correction.

Challenges and Criticisms

No system is perfect. Critics of the American trial system point to issues such as:

- Length and Expense: Trials can be time-consuming and costly for all involved.

- Inequities: Access to quality legal representation can depend on one’s resources.

- Jury Selection: Some argue that juries are not always representative or fully understand complex evidence.

- Plea Bargains: While efficient, plea deals may pressure innocent people to plead guilty.

Reform efforts continually seek to address these challenges and promote greater fairness and accessibility.

Conclusion

The trial process in the United States serves as a critical safeguard of rights and a forum for the peaceful resolution of disputes. While complex and sometimes daunting, the American trial system is designed to balance the interests of society, justice, and individual liberty. By understanding how trials work—from jury selection to verdict and beyond—citizens can better appreciate the significance and responsibilities of participating in the legal system, whether as jurors, litigants, or informed observers.

GNP

Leave a comment